Dissecting Totoro with Kishōtenketsu

I decided to start the term with something a little more challenging for my year 7 media class. These students are 12-13 year olds who have grown up with as much Gibli as Disney, so I figured they could handle having the curtain pulled aside on what makes the two most famous animation studios so very different, not just aesthetically, but philosophically.

And there is no better example than My Neighbour Totoro

I'm going to assume you have watched the film. If not, I'll wait while you go sort that out.

Miyazaki's 1988 masterpiece is awesome. It has a 92% rating on rotten tomatoes, and Roger Ebert calls it one of his 'Great Movies' Yet no one can really put their finger on what makes it work.

As Ebert himself points out, Totoro is:

...a film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No fighting between the two kids. No scary monsters. No darkness before the dawn. A world that is benign. A world where if you meet a strange towering creature in the forest, you curl up on its tummy and have a nap.

If we believe what the experts tell us about how stories work, then frankly, Totoro should be a forgotten oddity, not the cult classic it remains to be.

Even the students in my class who had never seen a Studio Gibli film before were captivated from the opening scene of two girls and their father arriving at their new farmhouse.

So what is going on? What makes Totoro work?

The answer of course, is Kishōtenketsu.

Time for a scene analysis. Like all good structures, Kishōtenketsu works on the macro and micro scale. I'll talk about the film as a whole later, but first, let's look at a seemingly inconsequential moment just after the family arrives at their new home.

Satsuki and Mei run inside, thrilled at the old house that their father tells them is most likely haunted.

Already we see a departure from the typical hollywood narrative, for instead of being frightened by this news, the girls are eager to find out more.

This is the Ki, or introduction moment of the scene. We've been introduced to an idea--old haunted house--and now we, like the sisters, want to see more.

They run through to the back of the house and find the supports of the verandah almost rotted through. This is the Sho, or follow on from the opening. And if you were brought up on western film, then you have a certain expectation about what happens next.

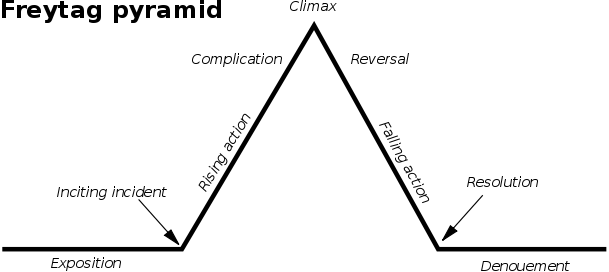

In the three act structure, visualised by the Freytag Pyramid, you can read the rotted wood as an 'inciting incident' and would expect that the next thing to happen will be the roof of the verandah start to fall, just when Mei is in harms way. The music would likewise turn ominous, warning us of the rising danger, and then, just at the climax, Mei's sister would heroically pull her to safety.

Instead, we have this:

The girls push the pillar back into place, with no change of music, no rising tension. It surprises us, and at first we cannot make sense of this moment. Will this be the classic double take, and just when the girls turn their backs, bam! down comes the roof?

Nope. Thrilled by the excitement their new house offers, the girls dance away into the forest.

Kishōtenketsu's third 'act' is Ten, a twist, as you can see above. This is a situation that momentarily unbalances our expectations, or confounds us with new information. Then the conclusion, or Ketsu, consolidates the scene, giving us perspective, rather than resolution.

The girls see a giant tree in the forest.

It seems intimidating, but the girls realise that like the wooden beam, this tree is not threatening, not something to fear.

That short scene at the start of Totoro is inconsequential to the rising action of the film. We never again see the threatening wooden pillar, so it is not the 'Chekhov's gun' some audience members might still assume. Yet it is crucial in understanding the unique emotional journey of the film as a whole. Taken as a part of the bigger film, the previous scene acts as one of the Ki moments of the first 30 minutes, introducing us to the sisters, their world, and an important tree. But not the conflict, for like Ebert pointed out, this film has none.

Ready for more?

Just like every scene in the film has this internal structure, the entire plot unfolds with the same four parts.

After finding soot gremlins in the attic--a scene that again confounds us with the realisation that these ghost creatures are benign--we meet old Granny, who, like their father, not only believes the girls when they tell her they have seen gremlins, but also explains how harmless they are.

Even when there is a scene of tension, such as the storm that howls while the family have a bath....

The moment is twisted around with laughter and the reiteration that while it can be wild, nature is not something to be feared.

Next we have the Shō, or the follow on, part of the film that builds detail around what we already know. The next day the family visit their mother, who is recovering from an undisclosed illness in a nearby hospital.

We would expect her illness to be life threatening, with the doctors telling us that without some hard to get medicine, the mother will die. Instead she assures the girls she will be home soon.

Mei, the youngest, continues to explore her yard while her father works inside and her sister goes to school.

And she discovers that there are more than soot gremlins in the forest.

Guided by her curiosity, with no thought of fear or danger, Mei follows these creatures into the trees.

and finds her neighbour...

Her older sister, Satsuki finds Mei, and although they cannot find their way back to Totoro, she believes that the creature is real.

Even their father does not discount Mei's discovery, and all three find the giant tree, respectfully asking the spirits of the forest to watch over them.

And we are shown that they will.

Next is the scene where the girls go to the bus stop to wait for their father. There is a storm, and for a moment the girls are worried.

Their father has missed the bus, and Mei eventually falls asleep on Satsuki's back. Again, we expect this to be a scene of rising action, with the girls, or their father, needing to overcome some problem to resolve the situation. But surprise!

Totoro arrives to remind us that even in moments of uncertainty, you should still stop and appreciate the wonder of nature and the beauty in something as simple as the sound of rain.

The catbus comes to take Totoro away, and, soon after, their father arrives late, but safe.

And they all go home, happy.

The macro Shō section of the film ends with a beautiful scene later that night, when the girls wake, run outside and meet all the Totoros.

They plant acorns in the veggie patch, and watch, as Totoro works his magic and the seeds transform into a giant tree.

Totoro then flies them high above the land, ending the scene with a final moment of consolidating Ketsu perspective.

Next comes the big twist of the film. The Ten moment on the macro scale.

After meeting granny and helping her pick corn, the girls receive a telegram.

Their mother is in trouble. Finally, it seems, we have the classic rising action we have been expecting.

The sisters run home, but Mei is separated and quickly becomes lost.

They are momentarily re-united, but Mei, certain now that her mother needs the corn to get better, decides to run away.

Satsuki searches for her.

And for a moment it seems like the worst has happened...

But Satsuki decides to ask the forest for help.

And finding her way to his hiding place, Totoro comes to the rescue.

Calling out for the catbus, that comes, and whisks Satsuki away to find Mei.

So far this section of the film has been built from micro scenes of Kishōtenketsu, each with an intro, follow on, twist and consolidation. Now is where the micro and macro converge, coming together in a final Ketsu section that resolves both Mei's rescue, and the bigger ideas of the film.

The sisters, together again, take the catbus to see their sick mother.

The do not, however, have the joyous cuddle we might expect. Their mother has no idea that Mei was missing, so there is no reason to upset her. Instead, they watch from the treetops, content, like their friend Totoro, to observe from afar.

And like Totoro, the sisters leave the adults a gift, a symbol of life in the form of the ear of corn taken from Granny's garden.

There is no climax of conflict, no major revelation or resolution of problems. But there is an ending, and it is more satisfying than any Disney 'happily ever after.'

The catbus takes the girls home and the final image is that of the Totoros, watching from their tree, seeing that all is well in the world.

Of course, there are those that think My Neighbour Totoro is about something completely different, and Miyazaki has never said he intentionally followed the structure of Kishōtenketsu. But using it as a lens to study the structure makes it clear that something very different is at work in the film than the majority of hollywood narratives.

As for my students, they ate up the class, loving the discussion as well as the film itself. The film that kept them laughing and wide-eyed to the very end.

And this, in the end, is the point of Kishōtenketsu.

About the only thing I agree with in the book 'Million Dollar Outlines' was the notion that we do not fall in love with genres of film, so much as the emotion different types of stories promise.

Fantasy, like her big sister, Science Fiction, has become more closely aligned to the Thriller and Adventure genres. It promises action, danger, magic and mystery. This is all great, but let's not forget what we fell in love with all the way back at the beginning with Tolkein, Lewis, and Le Guin. Wonder. It is the wide-eyed curiosity we feel exploring a strange new world that kept me reading SF as a child, and it keeps me here, writing it now. Wonder is a harder, more subtle emotion to convey, and it is easy to lose your way in a plot full of twists and battles and villains.

Kishōtenketsu reminds me to keep it simple.

T.B.

I'm going to assume you have watched the film. If not, I'll wait while you go sort that out.

Miyazaki's 1988 masterpiece is awesome. It has a 92% rating on rotten tomatoes, and Roger Ebert calls it one of his 'Great Movies' Yet no one can really put their finger on what makes it work.

As Ebert himself points out, Totoro is:

...a film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No fighting between the two kids. No scary monsters. No darkness before the dawn. A world that is benign. A world where if you meet a strange towering creature in the forest, you curl up on its tummy and have a nap.

If we believe what the experts tell us about how stories work, then frankly, Totoro should be a forgotten oddity, not the cult classic it remains to be.

Even the students in my class who had never seen a Studio Gibli film before were captivated from the opening scene of two girls and their father arriving at their new farmhouse.

So what is going on? What makes Totoro work?

The answer of course, is Kishōtenketsu.

Time for a scene analysis. Like all good structures, Kishōtenketsu works on the macro and micro scale. I'll talk about the film as a whole later, but first, let's look at a seemingly inconsequential moment just after the family arrives at their new home.

Satsuki and Mei run inside, thrilled at the old house that their father tells them is most likely haunted.

Already we see a departure from the typical hollywood narrative, for instead of being frightened by this news, the girls are eager to find out more.

This is the Ki, or introduction moment of the scene. We've been introduced to an idea--old haunted house--and now we, like the sisters, want to see more.

They run through to the back of the house and find the supports of the verandah almost rotted through. This is the Sho, or follow on from the opening. And if you were brought up on western film, then you have a certain expectation about what happens next.

In the three act structure, visualised by the Freytag Pyramid, you can read the rotted wood as an 'inciting incident' and would expect that the next thing to happen will be the roof of the verandah start to fall, just when Mei is in harms way. The music would likewise turn ominous, warning us of the rising danger, and then, just at the climax, Mei's sister would heroically pull her to safety.

Instead, we have this:

The girls push the pillar back into place, with no change of music, no rising tension. It surprises us, and at first we cannot make sense of this moment. Will this be the classic double take, and just when the girls turn their backs, bam! down comes the roof?

Nope. Thrilled by the excitement their new house offers, the girls dance away into the forest.

Kishōtenketsu's third 'act' is Ten, a twist, as you can see above. This is a situation that momentarily unbalances our expectations, or confounds us with new information. Then the conclusion, or Ketsu, consolidates the scene, giving us perspective, rather than resolution.

The girls see a giant tree in the forest.

It seems intimidating, but the girls realise that like the wooden beam, this tree is not threatening, not something to fear.

That short scene at the start of Totoro is inconsequential to the rising action of the film. We never again see the threatening wooden pillar, so it is not the 'Chekhov's gun' some audience members might still assume. Yet it is crucial in understanding the unique emotional journey of the film as a whole. Taken as a part of the bigger film, the previous scene acts as one of the Ki moments of the first 30 minutes, introducing us to the sisters, their world, and an important tree. But not the conflict, for like Ebert pointed out, this film has none.

Ready for more?

Just like every scene in the film has this internal structure, the entire plot unfolds with the same four parts.

After finding soot gremlins in the attic--a scene that again confounds us with the realisation that these ghost creatures are benign--we meet old Granny, who, like their father, not only believes the girls when they tell her they have seen gremlins, but also explains how harmless they are.

Even when there is a scene of tension, such as the storm that howls while the family have a bath....

The moment is twisted around with laughter and the reiteration that while it can be wild, nature is not something to be feared.

Next we have the Shō, or the follow on, part of the film that builds detail around what we already know. The next day the family visit their mother, who is recovering from an undisclosed illness in a nearby hospital.

We would expect her illness to be life threatening, with the doctors telling us that without some hard to get medicine, the mother will die. Instead she assures the girls she will be home soon.

Mei, the youngest, continues to explore her yard while her father works inside and her sister goes to school.

And she discovers that there are more than soot gremlins in the forest.

Guided by her curiosity, with no thought of fear or danger, Mei follows these creatures into the trees.

and finds her neighbour...

Her older sister, Satsuki finds Mei, and although they cannot find their way back to Totoro, she believes that the creature is real.

Even their father does not discount Mei's discovery, and all three find the giant tree, respectfully asking the spirits of the forest to watch over them.

And we are shown that they will.

Next is the scene where the girls go to the bus stop to wait for their father. There is a storm, and for a moment the girls are worried.

Their father has missed the bus, and Mei eventually falls asleep on Satsuki's back. Again, we expect this to be a scene of rising action, with the girls, or their father, needing to overcome some problem to resolve the situation. But surprise!

Totoro arrives to remind us that even in moments of uncertainty, you should still stop and appreciate the wonder of nature and the beauty in something as simple as the sound of rain.

The catbus comes to take Totoro away, and, soon after, their father arrives late, but safe.

And they all go home, happy.

The macro Shō section of the film ends with a beautiful scene later that night, when the girls wake, run outside and meet all the Totoros.

They plant acorns in the veggie patch, and watch, as Totoro works his magic and the seeds transform into a giant tree.

Totoro then flies them high above the land, ending the scene with a final moment of consolidating Ketsu perspective.

Next comes the big twist of the film. The Ten moment on the macro scale.

After meeting granny and helping her pick corn, the girls receive a telegram.

Their mother is in trouble. Finally, it seems, we have the classic rising action we have been expecting.

The sisters run home, but Mei is separated and quickly becomes lost.

They are momentarily re-united, but Mei, certain now that her mother needs the corn to get better, decides to run away.

Satsuki searches for her.

And for a moment it seems like the worst has happened...

But Satsuki decides to ask the forest for help.

And finding her way to his hiding place, Totoro comes to the rescue.

Calling out for the catbus, that comes, and whisks Satsuki away to find Mei.

So far this section of the film has been built from micro scenes of Kishōtenketsu, each with an intro, follow on, twist and consolidation. Now is where the micro and macro converge, coming together in a final Ketsu section that resolves both Mei's rescue, and the bigger ideas of the film.

The sisters, together again, take the catbus to see their sick mother.

The do not, however, have the joyous cuddle we might expect. Their mother has no idea that Mei was missing, so there is no reason to upset her. Instead, they watch from the treetops, content, like their friend Totoro, to observe from afar.

And like Totoro, the sisters leave the adults a gift, a symbol of life in the form of the ear of corn taken from Granny's garden.

There is no climax of conflict, no major revelation or resolution of problems. But there is an ending, and it is more satisfying than any Disney 'happily ever after.'

The catbus takes the girls home and the final image is that of the Totoros, watching from their tree, seeing that all is well in the world.

Of course, there are those that think My Neighbour Totoro is about something completely different, and Miyazaki has never said he intentionally followed the structure of Kishōtenketsu. But using it as a lens to study the structure makes it clear that something very different is at work in the film than the majority of hollywood narratives.

As for my students, they ate up the class, loving the discussion as well as the film itself. The film that kept them laughing and wide-eyed to the very end.

And this, in the end, is the point of Kishōtenketsu.

About the only thing I agree with in the book 'Million Dollar Outlines' was the notion that we do not fall in love with genres of film, so much as the emotion different types of stories promise.

Fantasy, like her big sister, Science Fiction, has become more closely aligned to the Thriller and Adventure genres. It promises action, danger, magic and mystery. This is all great, but let's not forget what we fell in love with all the way back at the beginning with Tolkein, Lewis, and Le Guin. Wonder. It is the wide-eyed curiosity we feel exploring a strange new world that kept me reading SF as a child, and it keeps me here, writing it now. Wonder is a harder, more subtle emotion to convey, and it is easy to lose your way in a plot full of twists and battles and villains.

Kishōtenketsu reminds me to keep it simple.

T.B.

Hey!

ReplyDeleteThanks so much for that :)

One of my very favourite things, written about so warmly and intelligently! I'm trying to write a story (a kind of fairy tale) with non-violent conflict resolution at the moment (that's what led me here!).

Hello mate ggreat blog post

ReplyDeleteHello matte great blog

ReplyDelete